Rocket City Rewind: The Story of Albert Russel Erskine

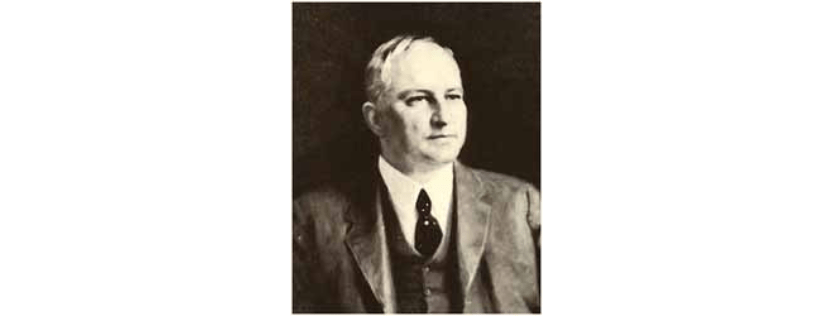

Albert Russel Erskine Sr., born in 1871 into a family with Dutch roots that settled in Huntsville around the turn of the 19th century, made his mark before committing suicide in 1933 under intense financial stress.

Before he left his troubles behind, he was regarded as one of the nation’s most prominent industrial magnates of his time, according to authors George Dickerson and Henry S. Marks who in 1974 penned “Albert Russel Erskine, The Huntsville ‘Boy Who Made Good.’ ’’

Erskine wound up living in South Bend, Ind., where he was a prominent figure who played a key role in civic matters when he was top man at the renowned Studebaker factory. Erskine left school at the age of 15, but became a captain of industry and left an indelible imprint:

- President, Studebaker Corporation (1919-1933)

- Treasurer and executive board member, Studebaker (1915-1919)

He held other positions during his time with the automaker:

- Vice President and Director, Underwood Typewriter Company

- Treasurer and board member, Yale and Towne Manufacturing Company

- Director, Federal Reserve Bank, Chicago

- President, Pierce Arrow Company

- President, S.P.A. Trucking Trucking Corporation

- Vice President and Director, National Automobile Chamber of Commerce

- President of the Board of Trustees, University of Notre Dame

- Director of a large South Bend bank

- Wrote “History of the Studebaker Corporation’’ in 1918 following the death of the firms last founders

- An avid sports fan and noted golfer, he initiated the Albert Russel Erskine Award for the top college football team

His legacy in Huntsville and South Bend remains to this day.

There’s the Hotel Russel Erskine downtown built between 1928 and 1930, which was once the center of local social activity. The group that built the hotel, now a run-down apartment complex, turned to one of Huntsville’s favorite sons when money ran short.

The hotel was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992.

There’s his family mausoleum he had built at Maple Hill Cemetery, elevated on a slight rise at the end of the road at the main entrance that’s adorned with a memorial gateway Erskine donated in honor of his deceased mother.

His pioneering ancestors were practically early-American royalty. A maternal great-grandfather, Albert Russel, was a colonel in Washington’s army during the Revolutionary War and was among the first settlers in Huntsville, originally known as Twickenham. His grandfather Dr. Alexander Erskine served as a physician in the Confederate army during the Civil War.

Clearview Cancer Institute, which sits on a tract known as Russel Hill across from the old Butler High School and is now home to The Rock Worship Center, was given a family name when Erskine’s ancestors settled there on what was then land outside the city limits.

At the time, according to Dex Nilsson in his story “Why is it named that?’’ those limits stretched all of a quarter mile in each direction from the public square.

He donated land for South Bend’s first 18-hole public golf course, Erskine Hills. It remains open today under the name Erskine Park Golf Course and the subdivision he built a mansion on is called Erskine Manor.

Business savant

Albert Russel’s meteoric rise in the business world was retraced in The Boy Who Made Good:

- Left school at the age of 15 and took a job as an office boy in a Huntsville railroad office, rose to the position of chief bookkeeper.

- At 27, moved to St. Louis for a position as chief clerk with the American Cotton Company and later became general auditor of the company’s operating department with responsibility for 300 cotton gins throughout the South.

- Joined Studebaker in 1911 and became president in 1915 and, in a footnote at findagrave.com, he “literally guided the Studebaker company from the ‘horse and buggy’ days into the position of a major player in modern auto production.”

In South Bend, Studebaker built the Erskine Six, which debuted in Paris where it was thought a market for smaller cars would be a hit, and later the Rockne, another compact six-cylinder that Erskine named after the fabled Notre Dame football coach.

Neither car succeeded.

Meanwhile, as the Wall Street crash of 1929 led to the Great Depression, Erskine failed to reduce operating cost and eventually inflated numbers of dividends the company was paying out. It all led to insurmountable debts for the company, which eventually went into receivership in 1933.

Erskine was forced out. The former wunderkind was also dogged by personal debt and had a heart condition that forced him to give up golf. The combination of his health and financial problems professionally and personally put Erskine under excruciating stress.

Albert Russel Erskine forged his name into American history as an industrial icon who was famous nationwide. He made most of his fortune in the North but, as the saying goes, you can take the boy out of the South but you can’t take the South out of the boy.

The Indiana mansion Erskine built in 1921 was named Twyckingham, possibly a twist on Huntsville’s original name and the place where he died from a self-inflicted gunshot on July 1, 1933.

In one of his suicide notes, which included burial instructions at Maple Hill, Erskine wrote these lines to his son as shared by the South Bend Tribune the following day:

“Nervous system shattered. … can not go on.’’