Madison Joins Multi-City Lawsuit Over Online Sales Tax Distribution

The Madison City Council has voted to join a multi-city lawsuit challenging Alabama’s distribution of online sales tax revenue under the Simplified Sellers Use Tax, or SSUT. The council also approved a resolution supporting the City of Tuscaloosa’s legal efforts to change how online sales tax dollars are distributed so that more revenue remains in the communities where purchases occur.

The decision follows a work session held last week, during which Madison council members received a detailed briefing on how SSUT revenue is collected and redistributed statewide. Tuscaloosa Mayor Walt Maddox and members of his staff led the presentation, outlining why Tuscaloosa initiated legal action against the Alabama Department of Revenue and how the current system affects municipal budgets and school funding.

“After conducting a work session last Wednesday night to learn how local Madison tax dollars are redistributed under the current SSUT law, the Madison City Council voted to approve a resolution supporting Tuscaloosa’s efforts in seeking appropriate application of SSUT law that does not divert significant tax revenue away from local governments and school systems in communities where taxable sales occur,” said Amanda Jarrett, MBA, APR, director of operations and communications for the City of Madison.

Madison now joins a growing list of cities challenging the state’s SSUT framework, which applies a flat 8 percent tax to online purchases made through eligible sellers. The system was originally designed to simplify tax collection from out-of-state retailers without a physical presence in Alabama, at a time when e-commerce represented a much smaller share of consumer spending.

City leaders argue that while online shopping has expanded rapidly, the SSUT distribution formula has remained largely unchanged and no longer reflects current purchasing behavior. Under the law, half of the SSUT revenue goes to the state and is split between the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund. The remaining half is distributed to municipalities and counties based solely on population, not where the purchases are made.

Local officials say that structure disadvantages fast-growing communities with higher household incomes and significant online purchasing activity. Madison Finance Director David Lawing previously told council members that the SSUT system limits the city’s revenue potential compared to traditional sales taxes.

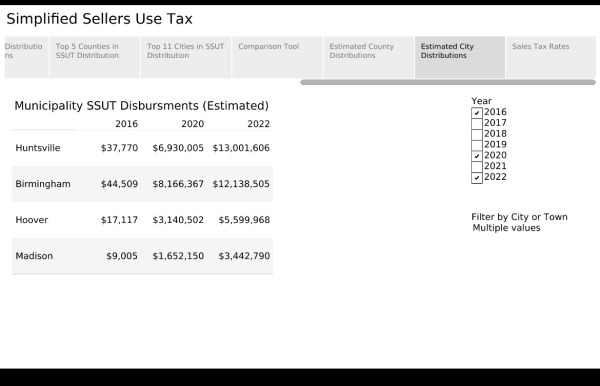

The impact is visible when comparing Madison to Huntsville. While Madison’s SSUT disbursements have steadily increased since the tax was implemented, the city’s growth has been far outpaced by Huntsville’s distributions, despite Madison’s residents generating significant online spending.

Estimated SSUT disbursements show Huntsville receiving more than $13 million in 2022, compared to roughly $3.4 million for Madison. City leaders argue that the gap is not a reflection of online purchasing behavior, but of a distribution model that favors larger population centers over the actual origin of taxable sales.

Madison expects to receive about $4 million in SSUT revenue in 2025, compared with roughly $21 million from regular sales taxes collected on brick-and-mortar purchases. City leaders say that gap underscores how heavily Madison relies on in-person sales tax revenue, even as residents increasingly shop online.

A local financial professional who wishes to remain anonymous said the SSUT structure also creates competitive challenges for local businesses. Large online retailers such as Amazon can participate in the SSUT program and collect a flat 8 percent tax statewide, regardless of local tax rates. By contrast, local retailers must collect the full local sales tax, which in some cities can be several percentage points higher.

“This creates an unfair advantage for online retailers on top of their ability to undercut local shops on price due to volume,” the professional said. “It also hurts smaller cities because the municipal portion of SSUT is distributed across all cities based on population rather than where purchases are made.”

Tuscaloosa Mayor Walt Maddox has argued that the SSUT system diverts revenue away from communities generating significant online sales and weakens local budgets over time.

“Alabama’s Simplified Sellers Use Tax takes revenue generated in our community and sends it elsewhere,” Maddox said. “Despite repeated attempts to work with the Alabama Department of Revenue, our concerns remain unaddressed, leaving us no choice but to take legal action.”

Mobile and Hoover formally joined the lawsuit on Monday, with additional cities expected to intervene. Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson has been one of the most outspoken critics of the SSUT distribution model, calling it a long-term threat to local governments and small businesses.

“We are giving Amazon and all of the out-of-state businesses a tax cut,” Stimpson said during a recent public address. “You are starting to look around and seeing mom-and pop stores shutter because they cannot compete.”

Stimpson estimates Mobile has lost roughly $200 million in revenue since SSUT was implemented nearly a decade ago. Hoover Mayor Nick Derzis said his city loses between $7 million and $10 million annually under the current system, money he argues should be reinvested locally in public safety, infrastructure and community services.

County officials, however, have pushed back strongly against proposed changes. Sonny Brasfield, executive director of the Association of County Commissions of Alabama, warned that counties would oppose any restructuring of SSUT, arguing the system is an efficient way to collect online sales taxes.

SSUT was established by Act 2015-448 and has since been amended to expand eligibility and include marketplace facilitators. While the system has generated significant revenue statewide, city leaders argue its population-based distribution model fails to account for where online purchases originate.

The disparity is visible in North Alabama. Madison is projected to receive about $4 million in SSUT revenue in 2025, while Huntsville expects nearly $20.5 million. Madison County is expected to receive roughly $15.1 million. City leaders argue the difference reflects population weighting rather than actual purchasing behavior, particularly in higher-income suburbs like Madison.

Huntsville City Council Member John Meredith has said the system affects both municipal operations and school funding. “It really has a negative impact on the city’s coffers,” Meredith said, “but also a tremendous amount on the schools.”

As the lawsuit moves forward, Madison officials say the city will continue evaluating the long-term impact of SSUT on its budget and coordinating with other municipalities. Supporters of the legal challenge argue that aligning online sales tax distribution with where purchases are made is increasingly critical as e-commerce continues to reshape consumer behavior across Alabama.